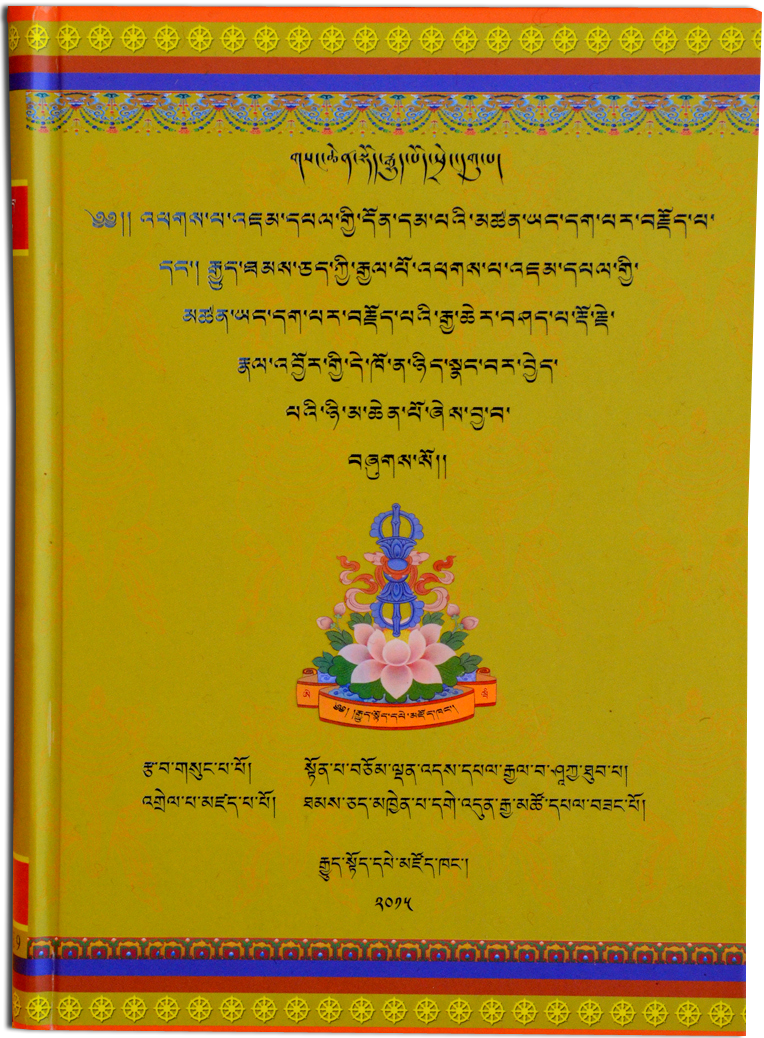

Preface to the text of Saying Mañjuśrī Names

By Kyabjey Prof. Samdhong Rinpoche

Inseparable from Teacher, Exalted Gentle Splendour Youthful—homage

[to You!]

Devoid of the coarse touch of afflictions, thus You are gentle;

Having knowledge obscurations exhausted, thus You are splendid;

Endowed with the sixty branches [of melody], thus You are melodious:

May You, Teacher Gentle Splendour Melody, kindly foster [us!]

1. The greatnesses of Saying Mañjuśrī Names

1. The greatnesses of Saying Mañjuśrī Names

The Victorious Ones (Buddhas) who have attained mastery over the pristine wisdom of Ominiscience, and who are restlessly motivated by great compassion, have shown various sets of teachings suitable to the tendencies, likes and thoughts of the trainees. All teachings are solely for leading the trainees towards the state of Omniscience; nonetheless, there exist limitless differences of the sequence of subject matter, profundity and vastness, starting from those showing the path of leading merely to the temporary [goals of] high status and definite excellences, up to those showing—in completeness and without mistakes—the integrating practices of the two stages, which bring about instantly the state of Conjoining within one lifetimes. Of these, the tantras of the Secret Mantra [Vehicle], in general, and the tantras of The Highest Integrating Tantra, in particular, are the greatly profound secret instructions, and of these, more so, the tantras of Guhyasamāja, Saṁvara and Bhairava, the Glorious Kālacakra tantra—which differs from other tantras, in ways of explaining—and others, are the core essence of the oceans of tantras, and that they are of distinct profundity and of greater blessings are not only asserted in the own words of Vajradhara, rather all accomplished adepts of The Land of Exalted (India) and of Tibet have in one voice admired to be so.

In particular, this Saying Perfectly The Ultimate-Meaning Names of The Exalted Gentle Splendour Pristine Wisdom Heroic Being—which is an excerpt from the chapter on meditative concentration, from [the tantra] The Exalted Illusory Net—is the root and core essence of all tantras, and was said,

being said and will be said, by all Buddhas of the three times, as a key to open the hundreds of doors of the definitive meaning, as [Saying Perfectly The Ultimate-Meaning Names of The Exalted Gentle Splendour Pristine Wisdom Heroic Being] itself says:

Profound meaning, the meaning is vast

And great meaning, matchless, very peaceful,

Virtuous at beginning, middle and end,

The Buddhas of the past have taught,

[Those] of the future too will teach,

The fully enlightened emerged now

Have said this again and again.

And, “The supreme owner of all tantras”—it has been said thus. Māhasiddha Nirupamarakṣita said, “…the four tantra-sets/ The essential tantra and the five/ Vajradhara has extensively taught./ This is the essence of the essence.//”

One may enter—by learning and reflection—in any tantra of The Highest Secret Mantra, but eventually without depending on the knowledge of the meanings of Saying Perfectly The Names, one would not know in completeness the stages of the path of the Vajra Vehicle—this appears to be the assertions of the valid beings (the great reliable teachers of the past), as The Spiritual Monarch Puṇḍarīka’sKālacakra Commentary, The Stainless Light, says, “Who does not know Saying Perfectly the Names, that does not know Vajra Holder’s pristine wisdom body;/ Who does not know Vajraholder’s body, that does not know the Mantra Vehicle.// By seeing this pivotal meaning, the Omniscient Gedun Gyatso Pelzangpo (His Holiness the Second Dalai Lama) said, “As Guhyasamāja is the root and basket of all tantras, likewise, so too is Saying Perfectly The Names—such is the thesis [asserted], solely.”

In the past, in The Land of the Exalted (India), when Sūtra and Tantra teachings were widely flourishing, if anyone knew Saying Mañjusrī Names the person is considered as knowing all Mantra scriptures, as evident from this: When Ācārya Candragomin went to Nālandā Monastery, he was asked what he knew; in response, when he said that he knew three things—Paṇiṇi Grammar, Praise in Hundred and Fifty Verses, and Saying Perfectly The Names—the glorious Candrakīrti then came to think of [Ācārya Candragomin] as a person learned in Sūtras, Tantras and languages.

By thinking of those reasons, also when the past accomplished adepts of Tibet compiled into texts and catalogued the entire translated Words of the Victorious One (Buddha), they placed [Saying Manjuśrī Names] at the beginning of all Tantras, as the first volume in the series. Situ Panchen said, “Placing at the beginning of all Tantras, as concordant to Non-dual Tantra, is greatly related.”

That this very distinct Tantra was regarded by all as valid and was greatly flourishing and pervasive, when the Secret Mantra teachings were on the rise in The Land of the Exalted, can be known from there being so many commentaries, commentarial explanations, general explanations, summaries and others, written by many adepts, and that the continuity of its manuscripts were found in all central and outlaying regions of India.

2. The place and time when Saying Manjuśrī Names was taught

The place where this Tantra of Saying Perfectly The Names of The Exalted Gentle Splendour is the great stupa of the glorious Dhanyakata, near the southern Splendour Hill; by emanating, in the lower level, Dharmadhātu Speech Mastery Maṇḍala, and in the upper level, Glorious Stars Maṇḍala, it was taught in Vajradhātu Maṇḍala.

The time when it was taught was on the fullmoon [day] of Kṛṣṇa month, simultaneous with Kālacakra Tantra. The commentators agree in the assertain that it was Candrabhadra, the emanation of Vajrapaṇi, who as well made the request and compiled [SayingMañjuśrī Names]. As regards the time when Kālacakra was taught, the Tibetan adepts have various assertions: it was the year following Teacher Buddha’s enlightenment, it was simultaneous with teaching of The Perfection of Wisdom Sūtras, at Vultures’ Heap-Peak (Gṛdhrakūṭa), it was the year the Teacher [Buddha] passed away into Pariṇirvāna (Beyong Sorrows), etc. There are many scriptural citations and reasonings to prove those assertions, nevertheless there is not the need to put into the time-frame of historians the the inconceivable secret benevolent deeds of Buddhas, which transcend the limits of space and time. Yet, if they need be fitted [into that frame], I see it as good to assert that it was the year prior to passing away into Pariṇirvāna; there are many reasons establishing that to be so, but due to lack of time [here to elaborate on them], I leave it untouched for the time being. In some differing translations of the Indian texts there is the mention that it is the fullmoon [day] of Viśākhā month—that is incorrect.

3. Translations in Tibet of SayingMañjuśrī Names

It appears that SayingMañjuśrī Names was amongst the early translations when Sūtras and Tantras were translated in Tibet, as this text appears in the Dhankarma Catalogue (ldan-dkar-ma), which the omniscient Buton regarded as the first Catalogue [of Kagyur and Tangyur], and it is also in the Phangthangma Catalogue (ḥphang-thang-ma). It appears that since those centuries Saying The Names was greatly flourishing and pervasive amongst the populace [in Tibet] because amongst the Tun-huang Ancient Manuscripts there were three varying texts of Saying The Names scribed at that time, which I have seen, and in those texts there are both variants: with and without the chapter on benefits. Also, the translations appear to greatly accord with Lochen [Rinchen Sangpo]’s translation.

At present, although the two translations—translation by Lochen Rinchen Sangpo and translation by Shong Lodoe Tanpa—are widely renowned, yet it appears that [Saying The Names] was translated many times by many translators in the past, as there appears at the end colophon of this text in the hand-scribed Phugdak (phug-brag) Kagyur, “on this there are also the translations by Lotsava Chimebum and Uepa Gargey. There also is a translation by Mangkharwa.”

In the aforementioned two Catalogues there were not translation-colophons to Saying The Names, but not only they were prior to Lochen, alreadly translated prior to Lochen were (1) The Lamp Clearly Illuminating The Meanings of [Saying] The Names, written by Paṇḍit Vimalamitra, translated by Lotsava Nyag Jñāna, a translator during the king Trosong Dhetsen, and (2) The Lamp Setting Ablaze Sun and Moon, a precious commentary written by Āchārya Padma[sambhava]—amongst Nyingma Kahma Gyaypa (The extensive Words, of Nyingma)—translated by Lotsava Kava-peltsek, a royal text of Trisong, hand-scribed by Vairocana. Of the root verses appearing in those commentaries there are very few which differ from Lochen’s translation; as such, it appears that Lochen had merely made changes to the earlier translations, but the colophon [of Lochen’s translation] says, “Translated and established, [for explanation and learning], by Indian Abbot Śrddhākaravarmā, Kamalagupta and the great Editor-Lotsava Rinchen Sangpo”. Besides, the subsequent commentators have recognised as “Lochen’s translation”.

In later times, during the thirteenth century, Shong Lotsava Lodoe Tanpa had re-translated [Saying The Names], which has many [parts] that differ from Lochen’s Translation and the root verses cited in those commentaries mentioned above; also, it greatly accords with the Indian manuscript/s of Saying The Names which are extant in India. It is mainly translated as a straight literal translation. In Kagyur editions of Peking, Narthang, Dege and Lhasa—printed in The Land of Snows and China—apart from Shong’s Translation of Saying The Names, not only there are not earlier translations, of Lochen and others, of Saying The Names, there is not even a mention of other translations extant. When printing and publishing compilations of Words and Commentarial Texts translated into Tibetan from other languages the best and the latest translation of each text on a subject was selected, the variant translations were not compiled—this could be to keep to minimum the number of the volumes. Whatever be the case, this has resulted in a big loss to Tibetan knowledge-heritage. Since the time there flourished the system of printing Kagyur and Tangyur although there have been a great positive outcomes, such as, preserving—from losing—the continuity of the texts; non-corruption by scribe’s omissions, additions and errors; easy access to the texts by all, owing to re-produced copying [of the texts]; and so on; but there have been the shortcomings, such as, the variant translations by many lotsavas and paṇḍits have faded from memory, and also the continuity of the texts have been lost.

It appears that in the so many hand-scribed Kagyur and Tangyur made in gold, silver, natural vegetable dyes, by the past generations of Tibetans of immense diligence and dedication—from the depth of heart and bone—there were many texts and variant translations which are not included in the Kagyurs and Tangyurs we see now, because, for example, in the Phugdak Kagyur—a set which is in Library of Tibetan Works and Archives, Dharamshala—there are 27 texts of separate subject-matters and of variant translations which are not in other editions; 9 texts of the same subject-matter with varying translations; 25 subject-matters (texts) which are not in any other editions of Kagyur. From this it would appear that there were many hand-scribed Kagyurs and Tangyurs throughout the central and outlaying regions of The Land of Snows and in the greater Mongolia country, those in which there were any number of subject-matters which the Tibetans of latter times have not seen nor heard of, and the possibility that there were many varying translations of Saying The Names. Moreover, in the hand-scribed Phugdak Kagyur there were lists of other translations—although the texts were not actually included—as cited earlier, which, even, are so helpful for those doing research into scriptural manuscripts. This hand-scribed Phugdak Kagyur was made between 1696–1706 at Phugdak Monastery, the monastic seat of The Accomplishments-Attained Ogyanpa Rinchen-pel, in Ngari region of Tibet, and it is a sublime distinct treasure.

The translation by Shong Lotsava is good and although it is the only translation that is in the Kagyur editions these days throughout the world, but in the regular prayer-recitations in most monastic centres of Tibet the translation by Lochen is verily the one still done at present. Not only that, starting from the Omniscient Gedun Gyatso [His Holiness the Second Dalai Lama], most of the Tibetan commentators had based [their commentaries] upon Lochen’s Translation itself—could it be because Shong Lotsava had not made changes to the early translations of the Indian commentaries, such as, The Stainless Light? There does not seem to be other reasons. Yet, in The Land of the Exalted most of the ancient texts were hand-scribed on tree barks, palm leaves and so on, thus because, in the successive copying of the texts, there were the likelihood of scribe-errors of omissions and additions and so forth—resulting in all kinds of varying phrases, words, spellings—those who did studies on the texts, who explained them, and those who translated them, had to cross check whatever manuscripts they could find, to indespensably do research in finding out the actual thoughts of the authors. Likewise, also the lotsavas (translators) of the past had consulted manuscripts from the central and other regions [of The Land of the Exalted], and others, and had made, again and again, changes and editing. As such, it is possible that Indian manuscript for the basis of Lochen’s Translation, and that of Shong Lotsava were two different Indian manuscripts.

4. Translations of Saying Mañjuśrī Names in other languages

Saying Manjusri Names was first translated into Chinese language by Ācārya Dhanapala, between circa 980AD-1000AD; by the Chinese translator Kin-stun Kh, at the beginning of the Twelfth Century AD. Including two other translations, it was known that there were four major translations in the Chinese language.

In the Mongolian language, the translator Dharma Kiraṇ(~prabha; Chos-kyi-wod-zer) translated Saying The Names, from Sanskrit, at the start of the Fourteenth Century and it was amongst the earliest Sūtras and Tantras translated into Mongolian language. Subsequent to that, there were translations when the entire Kagyur and Tangyur were translated from Tibetan language.

As for translation into English of Saying The Names, it was translated by the scholar R. Davidson, towards the end of the Twentieth Century; and there is the translation by Prof. Alex Wayman. There are these two translations, but it is not easy to translate such Vajra Words (of Saying The Names) into Chinese and English; as such, it is difficult for someone like me to say how qualified [those translations] have turned out.

5. The manuscripts of Saying The Names extant now in Sanskrit language

There are over a hundred varying hand-scribed manuscripts in Sanskrit language found [so far], as could be known from Catalogues, mentioned in the third edition of DHI journal of Central University of Tibetan Studies, Sarnath, Varanasi. Amongst them, it appears, there could be a manuscript hand-scribed on palm leaves—one of the earliest such hand-scribed manuscripts on palm leaves—of circa Tenth Century. Of them, the following is a brief description of the important reference manuscripts edited and published in 1994 by Banarasi Lāl, a Research Scholar at Central University of Tibetan Studies, Sarnath, Varanasi.

1) The first manuscript, hand-scribed on palm leaves, at The National Archives, Nepal; Manuscript Number: 4.2285. 2) The second manuscript, hand-scribed on palm leaves, at the same Archives; 5.164. It is assessed that these two were hand scribed in circa Tenth and Thirteenth Century A.D.

Apart from the two, the following are manuscripts of Saying The Names edited and published in Twentieth Century: 1) By the Russian scholar I.B.Mineof, published by St. Petersburg University, in 1885. 2) By Prof. Raghu Vira, published as the Eighth Volume of a hundred volumes series. 3) By the scholar Durga Dass Mukherjee, published by Calcutta University, in 1963. 4) By the scholar R. Davidson, published in 1981. 5) By Prof. Alex Wayman, edited and published [in 1985]. 6) By Dr. Banarasi Lāl, as mentioned above, with a comparative study of the hand-scribed manuscripts and all [modern] published [translations], and published by Central University of Tibetan Studies, Sarnath, Varanasi, in 1994. These are the manuscripts found and extant at present.

6. The textual size of Saying The Names

As regards the textual size of Saying The Names, all Tibetan Lotsavas had set it as of one anta (varta; bāmbo; one section), and there emerged several varying ways of setting the divisions into chapters of the actual text. Following the two commentaries—The Stainless Light and The Nectar Drop, The Bright Lamp—most Tibetan commentators assert thirteen or fourteen chapters, where the other chapters are the same, the difference being when the chapter on benefits is counted there are fourteen chapters; thirteen, if not counted. It is as follows:

From the first line “Then, the glorious Vajradhara/” up to “Body bowed, sat at the Presence/” (1:16) is the first chapter, the chapter on Request, comprising of sixteen verses.

From “Then, The Transcended Eliminative Śākyamuni/” up to “Transcended Eliminative One, this is request made well./” is the second chapter, the chapter on Response, with six verses.

From “Then, The Transcended Eliminative Śākyamuni/” up to “Looking at The Precious Great Crown, then/” is the third chapter, that of looking at the six species, with two verses.

From “The owner of words set into verse/” up to “Arapatsanāyatema:/” is the fourth chapter, the chapter on Illusory Display Net, Fully Perfected, three verses.

From “Thus The Buddha Transcended Eliminative One/” up to “The supreme of the modes of The Great Vehicle/” is the fifth chapter, the chapter of Praise to The Great Maṇḍala of Vajra Sphere, with fourteen verses.

From “Buddha, the great Vairocana/” up to “Vajra hook, great lasso/” is the sixth chapter, the chapter on Dharmadhātu Pristine Wisdom, with twenty-four verses and three lines.

From “Vajra Terrifier terrifies/” up to “The supreme of those with sound/” is the seventh chapter, the chapter on Mirror Pristine Wisdom, with ten verses and one line.

From “Perfectly there is no self, the suchness.” Up to “Pristine Wisdom flame greatly bright/” is the eighth chapter, the chapter on Individual Realization Pristine Wisdom, with forty-two verses.

From “The supreme accomplishment of wish’s meaning,/” up to “The great gem, the precious top/” is the ninth chapter, the chapter on All-Equal Pristine Wisdom, with twenty-four verses.

From “The object realized by all Buddhas/” up to “Mañjuśrī, supreme of the splendid/” is the tenth chapter, the chapter on Emphasised Activity Pristine Wisdom, with fifteen verses.

From “Bestowing the supreme, the Supreme Vajra—homage to You!/” up to “The very Pristine-Wisdom Body, homage to You!/” is the eleventh chapter, the chapter on Praise through the five Pristine Wisdoms, comprising of five verses.

Up to this are a hundred and sixty-two verses.

From “Oṁ sarvadharma…” onwards up to “…jñānagarbha ā:” is the twelfth chapter, the chapter on mantra, in prose.

From “Then, the glorious Vajadhara/” up to “Explained by all Completely Enlightened Ones/” is the thirteenth chapter, the chapter on Rejoicing, with five verses.

The Benefits explained subsequent to Chapter Thirteen (‘Chapter Eleven”) are in prose, and as such, they are counted as verses. In the Indian commentaries there appear the number of verses, thus resulting in the ease of proof-reading Saying The Names, without omission and excess of the verses, and this in turn has resulted in non-decline in the textual size up to the present.

7. The way the present text was edited

In general, Shong’s Translation is considered the best; not only that, in all editions of Kagyur, it is the sole version included. Nevertheless, most of those who do daily prayer recitation of Saying The Names—in Tibet’s major monasteries, and others—are accustomed to Lochen’s Translation only. Besides, in most Indian and Tibetan commentaries the Verses are greatly in accord with Lochen’s Translation. As such, both Translations are edited and presented in this text.

a) Lochen’s Translation [presented here] is based on on a short-folio edition in Tibet, which was in my hands not long after arriving in exile in 1959; this was compared with Phugdak Edition in Dharamsala Library (LTWA), and all of Verses appearing in both Indian commentaries: (1) the commentary, The Stainless Light, written by Puṇḍarīka; (2) The Lamp IlluminatingThe Meanings of [Saying Mañjuśrī] Names, written by Vimalamitra. In addition, it was compared with The Lamp Setting Ablaze The Sun and Moon of The Precious, a commentary on SayingMañjuśrīNames, written by Ācārya Padma[sambhava] and translated into Tibetan by Kawapel-tsek, which is in Nyingma Kah-ma (rnying-mai bkah-ma; Words [of Padmasambhava, in Nyingma)—it is different to any others in the ways of elucidation and [coverage of] terminology shortages, and thus it is distinctive. [Lochen’s Translation presented here] is also compared with Saying The Names in A Compilation of Praises and Prayers, published by Tso-ngon People’s Printing House, in 1996; although it is not Shongton’s Translation, but there are several verses which are not in accord with Lochen’s Translation, besides there are mantras—with Tibetan translations—at the beginning and end which are not in both Shong’s and Lochen’s Translations, and the name of the translator or the one who made changes is not mentioned; thinking that the changes and additions were made by a later-time scholar, comparison was also done with that.

When comparing with the six texts mentioned above, with unresolved doubts, efforts, as much as could be, were made in verifying [the verses], by comparing the Indian manuscripts in the latest editions of Saying The Names, published by Dr. Banarasi Lāl.

Whenever there are varying phrases and words in the manuscripts, those that appear to be correct are left in the text and those which are doubtful whether or not they are correct are shown in Footnotes, for the analyses of the intelligent ones. Where it is clearly understood that they are scribe errors, in any of manuscripts, they are shown in these ༼༽brackets with the notes describing them as incorrect, yet although they are ascertained as incorrect, but by not leaving them neglected, it is hoped that these too become worthy of analyses.

There are many varying end word of each verse—‘པ་’ (‘pa’), ‘པོ་’ (‘po’), ‘འཆང་’(‘ḥchang’), ‘བདག་’(‘bdag’), ‘ཏེ་’ (‘te’), ‘ནི་’ (‘ni’), and so on—which may appear as not much of an adverse factor for the understanding of the meanings expressed, but there have been in recent publications many printing errors of words of similar sounds placed instead in the wordings of the verse lines. If they were not corrected, by comparing the commentaries elucidating the thoughts and, the Indians manuscripts, there were many that could lead to greatly misunderstanding the textual meanings; take one or two examples: ‘བཀའ་’ (‘bka’; [Buddha’s] Word, Advice) and ‘དགའ་’ (‘dgaḥ’; Joy); also, the mistakes: ‘བརྟན་’ (‘brtan’; stable; firm) and ‘བསྟན་’ (‘bstan’; show), ‘རིག་’ (‘rig’; know) and ‘རིགས་’ (‘rigs’; species; lineage), ‘གྲགས་’ (‘grags’; renowned) and ‘དྲག་’ (‘drag’; fierce), ‘སྒྲ་’ (‘sgra’; sound) and ‘དགྲ་’ (‘dgra’; enemy), ‘ཀླུ་’ (‘klu’; Nāgā; Serpent) and ‘གླུ་’ (‘glu’; song), ‘འཇིགས་ཆེན་’ (‘ḥjigs-chen’; great fear) and ‘འཇིག་རྟེན་’ (‘ḥjig-rten’; world, the mundane), ‘གཞི་’ (‘gzhi’; base) and ‘བཞི་’ (‘bzhi’; four); for instance, there were these errors:

In the third line of the Verse 13, Chapter One (1: 13), for the correct “The unfathomable ones, joyfully/” (~ḥga-bzhin-dhu; joyfully/), it was written ‘bkaḥ-bzhin-du’ (‘according to advice’);

For the correct “Bearer of great patience, the stabilizer/” (‘brtan-pa-po’; ‘stabilizer’), 5: 9/3, it was written ‘bsten-pa-po’ (‘one who devotes to’), or, ‘bstan-pa-po’ (‘one who shows’);

For the correct “O Protector, the Great Supreme Knower/” (‘rig-mchog’) 1: 14/1, it was written ‘rigs-mchog’ (‘supreme species’; ‘supreme lineage’);

For the correct “Vajra renown, vajra essence/” (‘grags-pa’; ‘renown’), 7: 2/3, it was written ‘rdo-rje drag-po’(‘vajra fierce’);

For the correct “Great Gentle Melody, great sound/” (‘sgra-che-wa’; ‘great sound’), 7: 10/1, it was written ‘dgra-che-wa’(‘great enemy’);

For the correct “The Great Nāgā of all sentient beings/” (‘klu-chen-po’; ‘The Great Nāgā’), 8: 10/3, it was written ‘glu-chen-po’ (The Great Song’);

For the correct “The great frightening enemy, the supreme of the best/” (‘ḥjig-chen dgra; ‘The great frightening enemy’), 8: 16/3, it was written ‘ḥjig-rten dgra-ste’ (‘World’s enemy:’);

For the correct “Earth maṇḍala, the extent of the base/” (‘gzhi-ḥi-khyon’; ‘extent of the base’), 9: 4/1, it was written ‘bzhi-ḥi-khyon’ (‘extent of four’).

These listed here are mere representative examples. On such terms and words likely to be made mistakes of, it is important to take interest in, by those who do reading, studying and contemplation on this text.

Other than them, there are many errors of verb particles and genitive particles absent, and the two misplaced; likewise, varying ways of spelling words in the three tenses. Although there is not much likelihood of confusion as regards them, yet by hoping it would benefit those doing deep studies and contemplation, all these are shown in the Footnotes.

b) Shong Lodroe Tenpa’s Translation is of fewer printing errors. Comparative checks were done with four Kagyur editions: Peking, Narthang, Dege and Lhasa editions; apart from them, not only it could not be compared with other commentaries and manuscripts (editions), because of not being able to find the texts [of Saying The Names] in Cho-ne and LithangKagyurs, it could not be compared with them. Of the variations of phrases and words in the four Editions those which accord with the Indian manuscripts are left in the text, those which differ are shown in the Footnotes.

8. Appendices

At the end of Saying The Names there is a section explaining, in prose, the benefits, but, because there did not prevail a custom of regularly reciting it, it is not in most texts of Dharma Practices (Compilation of Prayers). Not only that, many Indian and Tibetan commentators had not written a commentary on this section, and Jey Gedun Gyatso (His Holiness the Second Dalai Lama) has said, “The chapter on the benefits was in Shong’s Translation but it does not appear in this widely known [text] which is recited at present, and also I see the wordings as well very easy to understand; [as such], like Nirupamarakṣita, I will summarize the [chapter] numbers into thirteen and explain:”. Here too the section on benefits is not placed in the main text. Yet, to make Saying The Names text complete with its branch, the section explaining the benefits is included here, both Lochen’s Translation and Shong’s Translation.

Amongst the followers of Tibetan Buddhism there are many who do the ancient tradition of daily reciting Saying The Names but rare are those who recite it in accordance with Ways of Reciting as advised in Tantras and Indian texts. Included here, therefore, prior to the main text [of Saying The Names], are The Instructions on Reading‘Saying The Names’, written by Kaśmīri Māhapaṇḍit Śākyaśrībhadra, who had been greatly kind to Tibet; The Instruction on Reciting Mañjuśrī Names, written by Ācārya Mañjuśrīmitra, the great Commentator of this text; two texts on ways of reciting SayingMañjuśrī Names, written by Gungthang Jampelyang, a Māhapaṇḍit (Greatly Learned [Adept]) of the degenerate times.

By thinking as [auspicious] sign and a dependent-link, also included, at the end of the text, are the single-page The Core Essence of SayingMañjuśrī Names, which is with seals of immense profundity and secrecy, and the two-verse Prayer Requesting His Holiness the Omniscient [Second Dalai Lama] to Live Long, composed by Khaedrub Norsang Gyatso.

9. Rejoicing and Expressing Appreciation

After taking into hands the project of editing—a qualified one which is in accord with the ways of modern manuscripts research—and publishing (a) the two varying Translations of SayingMañjuśrī Names, and (b) the extensive Commentary written by The Omniscient Gedhun Gyatso, there was a very short time, making it doubtful if the project could be completed in time. Yet, as the result of the fervent diligence—day and night—not minding of the hardships, the living Mr Tenzin Dhonyoe, who is proficient in editing works, the texts could be published just [in time]; this is a field of rejoicing and expressing appreciation.

For those who have rendered concordant assistances—Mr Lobsang Shāstrī, the Incharge of Texts, at Tibetan Library (LTWA), Dharamshala; Venerable Gyaltsen Namdol, an Assistant Editor, Research Section, Central University of Tibetan Studies, Sarnath, Varanasi; and others who have directly or indirectly rendered concordant assistances—I felicitate their kindness.

I express compliments to Chime Wangmo, a staff member at Department of Religion and Culture, for doing with fervent diligence, not minding the hardships, the complicated works of manuscript inputs. Likewise, I express compliments to the living Tenzin Lungtok and Jigme Pasang, for their various concordant assistances.

No doubt it is a difficult task to print texts in a very short duration of time, yet all—Proprietor and staff—at Surabhi Printers, Varanasi, have well accomplished the task as I wished, for which too I express, from my heart, appreciations.

This was expressed in a hurry, by Losang Tenzin (Kyabjey Prof. Samdhong Rinpoche), one with an ordained-practitioner’s form. For any mistakes, I request the forbearance of those with Dharma Eyes. Jaya Jagat!