Buddhism and Non-violence

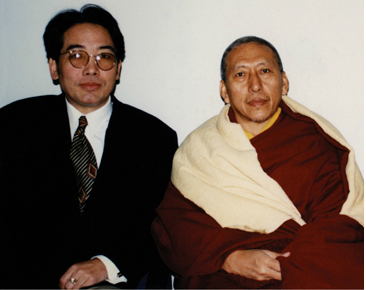

—A talk by His Eminence Prof. Samdhong Rinpoche

Tralek Centre, Melbourne, Australia

(A talk given, on 17 April 1998, at the request of the late Tralek Kyabgon Rinpoche)

Dear Dharma friends, my esteemed and respected friend Tralek Rinpoche.

I am very grateful to Tralek Rinpoche and the Centre for giving me this opportunity to meet you all this evening and have some exchange of ideas. Several years back Tralek Rinpoche asked me to come here particularly to be with him for few days and in the Centre; he asked me personally and also wrote to me but I was not a free person in India, I could not avail that invitation, that opportunity; despite full willingness, I could not fulfill Rinpoche’s wish.

This time I happen to come to this side of the world to fulfill some of my academic commitments in the University of Tasmania, and in coming to this side I added one more week to meet with the Tibetan community and Tibetan supporting people in Australia, and to have brief visits to few places, thus giving me this opportunity to see Rinpoche and you all; [and also] because I havea great deal of respect and admiration for him, for many various reasons.

With this evening’s discussion I have to clarify that this is not a Dharma talk,….this is just an academic teaching discussion. I stopped giving Dharma talk long ago, perhaps last ten years. I never accept to indulge in Dharma talk because to give a Dharma talk carries a lot of responsibilities and also certain norms which has to be fulfilled and I am unable to come up to the marks of those conditions; so, I thought better not to give any Dharma talk.

And particularly today I could not avail any preparation for presentation of this discussion; I was informed to discuss about Buddhism and non-violence. That’s good for me because I try to devote myself in promoting the idea of non-violence.

Non-violence is not a matter exclusively related to any religious tradition. Even a secular life, day-today life, for a non-believer, irreligious people who have no willingness towards practice of Dharma, also need non-violence because violence and non-violence affect our life directly; not only our lives but theyhave effects on the lives of the entire sentient beings. Particularly in this modern age, on the verge of completion of present century and entering into a new millennium, when humans have achieved a great deal of scientific and technological development which has made this world very small and everything has been globalized, and in the process of globalisation of everything, violence becomes so powerful that it takes various forms and shapes and which indeed endanger the basic survival of the humanity and the earth. It is for that reason any reasonable person or any wise person has to think of this more seriously. Not only from the religious point of view but also from secular point of view—it is worthwhile to discuss.

So for that reason I have devoted my energy and my life for the promotion of non-violence among the humanity. As I mentioned before, I could not prepare an organised thought to present the things before you, and at the same time I have limitations with my language skills—as such, do please bear with me. I have to find the words with some difficulty and effort. The English language has never been my medium of communication or expression. I live most of the time in India, that also in the northern part of India where the usage of English language is seldom and rare. My own language is Tibetan and my daily usage with other people is Hindi or any other for that matter in Indian languages. With conversations in English, I have to use it often only when I am out of India and with English-speaking community. With these few prologues or kind of preface to my talk, now I will try to go into the given subject, the given topic to be discussed.

Buddhism is a name given to the Dharma, doctrine,preached by Buddha. I don’t know, strictly speaking, the Buddha Dharma can be termed as ism or religion; that is a matter for discussion. The academic people today discuss a lot whether the teachings of Buddha canbe considered as a religion—I am not going into that controversy.

We talk about religion in the sense of spirituality or in the sense of path, therefore we need not indulge here in the interpretations of the word. In any case, the word is not the meaning, the word is not the fact. The focus of Buddha’s teachings is to examine the inner self, to look inwards and to realise the nature of life or the nature of self or the conditions of the individuals. When we look into the conditions of the individuals, you will realise the reality of the unenlightened individual that is full of misery.

Siddhartha, when he encountered with the facts of life—old age, disease, decay and death—he was sensitive enough to relate those facts to one’s own life. He asked his companion, his charioteer,whether these facts—the reality of decay: birth, old age, disease, decay and death, apparently horrible things—come to a few select people or do they come to all living beings. His companion replied, “My lord, it is the nature of all living beings, that whoever takes birth is bound to meet with decay, disease, old age and death. No one is exempt, no one has escaped from this nature, from this reality.” Then Siddhartha thought, in that case the youthfulness of his body, the spirit, the energy, the enthusiasm and the enjoyment of his kingdom, his life, his family, relations, are essenceless because it is certain that they will decay, all that will disintegrate and disappear,they are impermanent. Impermanence itself is a kind of horrible misery, pain, and nobody wants to encounter it, face it.

Then Siddhartha pondered upon whether there is any possibility of getting freed from this. In this process of examination he thought that all this misery does not occur without cause, it is not given by someone else, it comes because of the presence of cause, causes and conditions. The causes and the conditions can be eliminated, they are also not permanent. They can be eradicated, and that there are means for the eradication. There is a way, there is a path. All miseries come out of their causes, karmic forces, force of action, which in turnis caused by mental defilements, kleśa: hate, greed, attachment, which come out of ignorance; ignorance which deprives your mind from seeing and perceiving the things as they are. Thereby a great deal of delusion and illusion arises and which further generates the defilements of mind.

Although defilements of the ordinary mind are also temporary, they can be eliminated if you practise the right path and the right methods. You can acquire the wisdom which is the opposite of the ignorance and thereby the darkness of ignorance can be eliminated and subsequently the entire mental defilements can be eradicated. And,when the defilements of the ordinary mind areeradicated there would not be any further accumulation of karma, actions, accumulation of force of action and the cycle of rebirth, disease, decay, death and so forth. The bondage of birth and death will completely cease and the person can go into freedom and attain enlightenment. This is based on the principle of cause and effect, of causality. By realising this fact through a middle path approach, this is the way to attain enlightenment.

Buddha recounted the way, the path through which he has traversed and got enlightened. This he taught us in the form of various teachings which were later on compiled and formed the three baskets of Buddha’s teachings, the tripiṭakas, and fortunately the lineage of these teachings is alive, we still have access to it.

Buddha talked about the principle of causality, the causality of karmic force, and the result of the karmic force, the theory of karma (action) and its effects: if you accumulated virtuous karmic force, good karmic force, the result will be happiness, fulfillment and satisfaction; if you accumulate non-virtuous deeds, negative karmic force, the result would be misery, pain, dissatisfaction, frustration, disaster and what not; the relation between good karma, good action, and its result as happiness or peace, and bad karma and its result as misery or chaos. This is not a mythological story, it is a verifiable fact. You can verify it though experiment, you can verify it through your rational mind. You can verify it through logic and inference, and you can verify it from your own valid experiences.

Buddha therefore says violence is negative, violence is a non-virtuous act and violence accumulates the force of non-virtuous actions. Any kind of violence is not good. Therefore every sentient being, particularly the human beings who have the capacity of rational mind, power of thinking, power of analysing, to examine things and discriminate the good and bad, virtuous and non-virtuous, must try to avoid act of violence and must practise non-violence as a way of life, as a practice of spirituality. If our basic human responsibility, if that responsibility, is not fulfilled, then you cannot claim yourself as a human being, as a rational person, as a person who has the ability to discriminate between good and bad, right and wrong. With this background Buddha spoke about non-violence at various levels and at various stages.

Before going into these details, one thing I like to say with all the force of emphasis is that non-violence is not a negative thing. Non-violence is not a mere absence of violence. Non-violence is not a passive thing. Non-violence is one of the most difficult yet one of the most active and forceful actions.Just to remain ideal or not acting any kind of violence is not non-violence. There are many violent persons and violent animals, even the most horrible terrorists, they do not act violently at all times: during their sleep or during their unconscious state or during their leisure time they may not indulge in violent actions. But that simple absence of violent act does not make that person non-violent. That does not mean the person is practising non-violence.

Non-violent action can be performed only a person who has refrained from violence intentionally, by knowing that violence is a non-virtuous action and that I must not do so. The person who has the capability of injuring or causing pain to others and there are provocations or temptations to commit such acts, yet that person refrains from indulging in such acts; knowingly, intentionally and with full awareness and effort to refrain from that act is a non-violent action, non-violent karma. And that is absolutely a positive action and that is….a most difficult action, that is not passive or action-less.

Having said so, why should someone practise non-violence? The reasons for practising non-violence differ from person to person in accordance with the development of that person’s mind. In Buddhist tradition, particularly in the tradition of Dīpaṅkaraśrījñāna, we classify the spiritual practitioners or the religious minded people into three categories: adhama puruṣa,madhyama puruṣa and mahāpuruṣa, the beginner, the middling person, and the excellent person. The beginners are mostly concerned with themselves and that too for a few lives to come. A person who is only concerned with this life’s affairs, is not a religious person. That person can be a good person but that person is not a religious person. That person has not entered the path of spirituality or path of Dharma.

Of those, whosoever have entered the path of Dharma, the beginners think about the coming life,that after death what kind of life they would take; and for that—for attaining good rebirth—Buddha taught the practice of the ten virtuous acts, which are conducts or ethics, to avoid non-virtuous acts, so that you may ensure that your future lives would be in the higher realms of rebirth.

The reason why you should not indulge in violence is because violence is a non-virtuous action, it is an akuśala karma. Whatever form you act in violence is bound to bring negative karma and if you accumulate only negative karma then you would be reborn in the lower realms and you will not have chance to practise Dharma and thereby most of the coming lives will be to descend to the lower rebirths, in perpetual misery. Therefore, for your own sake, for your own happiness, for your own rebirth into the higher realm you should refrain from violence and you should practise non-violence. That is quite simple selfishness and not very high-level thinking or that a not very virtuous thought goes behind it; yet still non-violence is being practised.

Then a person evolved more elevated into the path of Dharma and path of spirituality, realises that even ensuring a higher rebirth in the next life is not enough until and unless you do not get freedom from the bondage of defilements and karmic force. Your misery can never end within this saṁsāra, the cycle of mundane rebirths; you may be reborn in the good realms or you may be reborn in the bad realms, you are still bound to face other sufferings and pain. The worldly pleasure is just a change of pain and we call it misery of change, pariṇām duḥkha, and that is also in reality not happiness, not peace. Apart from that even if you are reborn in the realm of the highest stage of worldly upward elevations, even if you are born in the realms of dhyāna, the peace and stability of mind remains only for a specific period of time and thereafter you have to be reborn in a different realm. Bondage itself is a kind of misery, saṁskāra-duḥkha, the result of karma and kleśa, actions and defilements.We always have to carry this contaminated aggregate, the composite of mundane body and mind, without our wish, without any freedom; that itself is a great deal of misery. So, to achieve durable and permanent peace in the form of liberation, nirvāṇaor arahathood or prateyekbuddha, that is the cessation of karma and kleśaand retiring into the bliss of nirvana, emancipated from the bondage of saṁsāra.

To get to that stage you have to stabilise your mind into meditative concentration, and for that matter, to refrain from the gross disturbance of mind, the action of violence; unless and until you refrain from that gross disturbance of mind in the form of violence you cannot achieve samādhi,or the concentration of mind. If you could not achieve the concentration of mind you cannot generate the wisdom, the perception of the reality or the perception of truth, through which you could eliminate the source of the mental defilements, which is ignorance. So, in order to achieve this,there is the threefold path to nirvāṇa: śila, ethics; samādhi, meditative concentration; and prañjā, wisdom. Prañjā is squarely dependent on samādhi, the concentrative mind, stability of mind. Samādhi is fully dependent on śila, ethics, to refrain from violence, and for that matter you have to refrain from the acts of violence. The reason is different here, here at the middling person level, the reason is that your objective is nirvāṇa, the cessation of karma and kleśa; and to be able to do so you have to perceive the truth, and for that perception by mind you must have the stability of mind;the stability of mind is necessary for elevation to spiritual attainment. Your objective is much higher than that of the ordinary or a beginner who practises non-violence only for the sake of taking birth in the higher realms. Here, with the middling person, the objective is higher, larger, and thereby the practice of non-violence is much deeper than the first one.

Here the basic objective is liberation of oneself. One feels disgusted with the perpetuation of misery for countless times, years, aeons, countless births and rebirths; one just want to get rid of that. Yet it is just retiring into bliss and peace for the sake of oneself, for the sake of getting rid of the misery which oneself experiences.

When the thought goes to the higher level, that of mahā puruṣa, the great capable person,the level of a bodhisattva, who has the basis of mētreya and karuṇā, love and compassion, for others; with the great compassion—mahākaruṇā—as the basis, which takes in the focus of thought the entirety of sentient beings without any discrimination; also the willingness and shouldering of the responsibility to get rid of the entire misery of all sentient beings. Such a great compassion further generates bodhicitta, the determination to achieve Buddhahood through countless efforts by accumulating the collection of merits, puṇya saṁbhāraand by practising jñānasaṁbhāra, that is, wisdom, generating wisdom and through which one gets rid of the defilements of the ordinary mind, kleśaāvarana, and the seeds of defilements of mind, jñānaāvarana. For the purpose of getting rid of them, a greater force of wisdom has to be generated, and for that a greater amount of practice of all the pāramitāsādhana—practices of the perfections—are required; and for that matter, the purpose of the practice of non-violence is absolutely not for any selfish end, not for the benefit of self—it is entirely for the benefit of others.

Violence creates pain,therefore one must not indulge in violence. One has the responsibility to lead others to enlightenment, to Buddhahood, and towards that aim one has to accumulate a great deal of practice of perfections, pāramitās, the six pāramitās or the ten pāramitās. Each practice of the perfections depends on the stage of non-violence, the level of non-violence, how deep, how high and subtle level. If there is no contamination by selfish motives, then one’s practice of non-violence is much higher. Here the practice of non-violence is for the sake of others, not for oneself. By this way you can say that if we sum up the entire teachings of Buddha, non-violence is the essence of Buddha’s teachings. In Caturśataka, The Four Hundred Verses [on the Middle View], it was exactly said that if asked about the totality of Buddha’s teachings, the answer would be that the totality of the Buddha’s teachings is non-violence.

So in this way the Buddha taught us to practise non-violence at all levels, whatever development of the mind you have reached, and at what kind of path you are practising, and what kind of objective you have set out. You have to practise non-violence, because there is no other way to practise Dharma otherwise. This is non-violence from Buddhist viewpoint. Even for a non-believer, who does not believe in Dharma or any kind of religious traditions, an entirely secular person, that person, given he/she also is a good human being, can relate that one never wishes to have misery or pain for oneself, likewise everyone is equal as nobody wishes to have pain or misery or suffering. If oneself is not ready to face any suffering then how one can have the right to cause injury, pain, misery [on others]….(Note: recording indistinct here)…and educated people talk about equality, democracy, individual rights, human rights and so forth. Unless and until you could explain the supremacy or the necessity of non-violent action at all levels, at level of individual, at the level of groups or at the level of nations, continents and countries and so forth, you can never materialise or implement any kind of rights in reality. You may talk about it very eloquently but that would be total hypocrisy, total lie. You will never be able to implement or establish any individual rights or social rights.

Of course, from the Buddhist teachings’ viewpoint we do not attach much importance to rights, we attach importance to responsibilities and duties. Everyone has to look after one’s own responsibilities and duties towards others and particularly towards the entire universe. His Holiness the Dalai Lama always talks about universal responsibility. His universal responsibility is his way of translating the essence of bodhichita into English language. The essence of bodhichita and the essence of mahākaruṇāis a kind of feeling of universal responsibility. If you ignore that kind of universal responsibility, you will not be able to establish or protect any kind of rights. In the absence of responsibility of oneself, how can we impose the rights of others. That is a simple logic.

In the traditional terminology, when we define violence, it is mostly defined in the realm of individual actions and direct actions of violence. Ofcourse, any kind of action which is initiated by a bad intention, intention of greed or hate, is going to result in act of violence. But we have not elaborately discussed about the indirect or structural violence. Perhaps in the ancient days there was not much social structure which could result into a great deal of violence. Today the violence has many forms. Violence in the form of discrimination among different nations, in the form of war, destruction and terrorism,are quite obvious. But there are many of indirect violence, which cause a great deal of hardship to the humanity: violence in the form of economic disparity, in the form of political domination and social domination, exploitation—socially, economically and politically; violence in the form of destruction of environment and ecosystem, in the form of competition.

Violence in the form of competition, in my opinion, is a very deep violence, which is very difficult to avoid. Competition becomes a part of life in every sphere, particularly economic systems. I sometimes laugh on hearing the expression “free and fair competition.” It itself is a contradictory term. If you are competing with others, how can you be “fair,” how can you be “free”? “Free and fair” is out of question when you are in a competition. Competition means to get ahead of the other, to defeat the other, win oneself, without which there is no sense of competition. Competition is violence. In many of diplomatic relations—diplomatic relations between nations or countries or government—of course there will be a lot of competition. Even simple relation of friends, between family members, between parents and children, between teachers and students, there are lots of violence, unfaithfulness, unfairness in our relation. Sometimes we feel that without violence we may not be able to maintain the social relationship. Today, social relationship requires lot of untruthfulness, lot of false statements in the name of courtesy, in the name of manners, in the name of maintaining the relationship, and so forth. All these are quite obviously violence.

In totality, if the majority of people cannot be convinced to practise non-violence, not only the future of humanity but the future of earth and the nature, the world itself cannot survive. That’s quite clear. The human mind has become so aggressive; people are not satisfied with conventional and traditional violence. People claim that now they have the capability of reaching the moon and other planets and stars, and the technological ability knows no bounds. But if we look towards the uncivilized“ savage man” in the stone-age and in the pre-civilization they fought with each other with stones or using small iron weapons, but they fought each other, killed each other, they were aggressive. Today, the spirit or the intention or inclination to fight is still there. Today we fight with atomic bombs, chemical weapons and many other such things by which hundreds of thousands can be killed within seconds; Hiroshima, Nagasaki, the disasters we have witnessed by our own eyes, these are human “developments,” and in such circumstances, whether a religious person or irreligious person, how can we justify our actions? What is the “development”? What is the “advancement”? The same hatred, the same greed, the same intention to dominate over each other, and we are still in the habit to dominate others. “Might is right” still remains very much in the minds of people.

Therefore, the more danger is that we have accumulated and achieved ability of violence and destruction in such unprecedented scale which could destroy the entire living beings on this earth, and the earth could be blown up into pieces—that kind of power we have accumulated. At the same time the anger, the hate, the greed, the ignorance, we have it all intact without any small quantity lessening; perhaps much more than the “savage men” used to have. As such, the realisation of the importance of non-violence is the only ray of hope, only way to save the humanity. That is the point that we can discuss and ponder.

I am sorry I have taken up much of your time. So I must stop here. Again, I am sorry for not being able to organise my thoughts and to put things with lesser words. I should have been able to talk these things in five or ten minutes…(laughs)…but I have taken much of your time by repeating the sentence again and again. So I apologise for that. There is still little time left. I would welcome any comments or questions perhaps. Thank you very much.

Q: We were struck by your comment on competition, and I suspect many people in this room have been because in Australia or I am sure in the other western countries that you would have visited we are all being confidently told we have to be more competitive individually as workers, competitive against one another in order to keep our jobs, and I imagine most people here would have gone under the same experience in the last few years of either being made redundant because they were judged not competitive enough or having watched their work colleagues being made redundant. But as well as that ofcourse we are pressured to become more competitive against other workers in other countries, particularly in the Asian region. I just wonder what you would have to say perhaps about how to practise non-violence in this economic context that we are all in.

Prof. S. Rinpoche: I have no answer to that question, because economy and wealth have taken the central place of all the human values and perhaps that is the essence of Modernity, and if I reject that, you would simply say, this man is of unsound mind or perhaps backward minded. So, I cannot argue with sophisticated modern person. I suppose the modern people are rational and in that rationality ‘self’ is much more important than others. Thereby one must achieve as the winner in a competition and he or she must stand out on the top, and if that is the rationality, then I have nothing to say. My argument is exhausted there, my rationality finishes there, and can’t argue.

But one question remains there, that is, what is the end of competition? If there is no end to competition, then two questions would follow further: then, what is the purpose of competition, and what is the possibility of competition? That is one side of the theme, the other side is, how one can justify a competition as non-violence. If competition is unavoidable one must admit that violence is also unavoidable. We must not talk about violence, let violence be there and that it be evil; one may say so that it is a necessary evil. Today many people have reconciled with necessity evil and they say there is no way out.

A few months back I was discussing with some Indian scholars, perhaps one month back. They say, your proposition is impractical because we have to survive. If you have to survive you have to compromise with many things and without competition or without violence you cannot survive. It sounds to me quite rational. But I asked them one question, “What is the compulsion for you to survive, if there is no way to survive as good human being, then what is the purpose of survival?” Surviving on the cost of others—that sounds unreasonable to me. Either of us has to survive by killing the other; then how should we decide who should be killed and who should survive, is the logic that would ensue. Everyone would argue I should survive and you should be killed…(laughs)…and the other person would say the same. There would be no end to it. It cannot be justifiable by logic. That again comes back. Whoever is mightier would kill the weaker and the mighty would survive on the cost of the other. So the question is whether there is a method of living equally, ‘Live and let live’. If you cannot serve others you must live and let the other live. If you have to live on the cost of others then what is the purpose of living! That is also one of the questions. If you think your survival is must and you have to compromise with the violence or with harming others, then that may be your logic. I have no answer to that. So therefore, your question is difficult and I have no answer to that.

Q: Rinpoche, How can we promote non-violence in a secular society?

Prof. S. Rinpoche: I used to think how it is possible for “culture of non-violence.” Sometimes I used to question against that expression too. The word “culture” is a very modern expression or a modern product. Now the word “culture” is used for various things. Two years ago a seminar was organised by UNESCO and they talk about “culture of peace” and “culture of war.” I was a minority of one in that seminar and I said there cannot be a “culture of war.”Culture” means something civilized and war is uncultured. There cannot be a “culture of war” and of violence. If cultured society is there, that means the society is free from violence, free from the rudeness or “unculturedness.”

Our way of looking at things are very much conditioned by Indian thought process or Buddhist thought process. In Indian language we talk about saṁskṛit, or prakrit. Prākṛit is with nature, with good effort, good refinement, things becomes of cultured natureor saṁskṛit. When the culture decays, then we call it vikṛit, uncultured or the distorted things. So, by that way, I can never think of “culture of violence” or “culture of war.”

Non-violence in civil society should be possible if everyone thinks of two things: the responsibility of oneself to all the universe, and try to fulfill that responsibility. Secondly a sense of equality must prevail, and for that matter another requirement is, to have individual freedom. Individual freedom is absolutely essential for realisation of equality and realisation of responsibility towards others. In that individual freedom, we must have the freedom to think by ourselves, particularly to decide what is our need. I am losing that freedom today because today my need is decided by the producers and manufacturers. They brainwash, indoctrinate me,….You need this, you must have this, you must purchase this; whether you work ten hours or twenty hours or daily, you must earn money and be able to purchase this because what you have is outdated; that is last year’s thing and you must purchase some new equipment and something, something. Your food taste, your requirement for nourishment of your body, what arethe suitable clothes for your body, what kind of education, what kind of book you should read—all these are decided by the publishers and by the tailors and the restaurant owners. You are conditioned by them….the freedom of the individual to decide or think for oneself is lost in today’s world. We shall have to regain that individual freedom. If that individual freedom is regained then everybody begins to think for themselves without any outside influence, then there will be no problem to establish a non-violent society.

I tried to suggest a system of economy based on truth, non-violence, eco-friendly and based on genuine needs. Gandhi has said very clearly that Mother Nature or Mother Earth can produce more than sufficient to satisfy your genuine needs but this Mother Nature can never produce to satisfy your greed. Today nobody thinks about their need, everybody thinks with greed. Greed is always on the side of the increase. That’s why the situation today is that, 80 per cent of the world resources are utilised by the 20 per cent, the rich people, and the 80 per cent of the population has to survive on the 20 per cent of the world’s resources. That is our disparity because of competition, because of loss of individual freedom and so forth.

I am sorry, I don’t know if I have time to say but I see the things like this.

Q: One more question?

Prof. S. Rinpoche: That’s the last?

Q:Yes, last.

Prof. S. Rinpoche: (Indicating to the Organiser) He is my guardian here. So he decides. As long as I am in Australia he will decide the time schedule for me. (laughs)…I have no individual freedom to decide…(laughs).

Q: Rinpoche, Thank you very much for your inspiring words. I was wondering how you fit in your views about non-violence in cases of self-defence? Can violence be justified to defend oneself against physical or other forms of harm?

Prof. S. Rinpoche: That is a very traditional question, which has been dealt in length by various religious traditions. A number of Indian thought traditions think that violence in self-defence is justifiable. That is one statement, and another statement is that, violence in self-defence is not a violence. The third kind of statement is, violence in self-defence is a duty for the individual. So these are various thought traditions developed in the Indian thought traditions.

But in Buddhist viewpoint, even in the case of self-defence violence is not permissible, violence is not justifiable and for that matter the Buddhist teachers use argument in a number of different ways. First, if power of non-violence, power of compassion and love in your mind is developed enough then the question will not arise that you need to defend yourself through violent act. The necessity of self-defence arises because you are not non-violent; if you become completely non-violent, there cannot be any danger to your life, to your body; apart from the natural things there cannot be unnatural danger to your life. If there is no unnatural danger to your life then the question of self-defence doesn’t arise. The necessity of self-defence itself is a symptom of violence or a result of violent mind. Therefore, if you are a violent person you cannot be able to defend yourself, even you might be apparently be able to defend yourself through a violent act but that is not the end of the story. You might be able to defend yourself once or twice but you will always be endangered and your defence would be proved inadequate.

Sometimes my thought goes and I might agree to that argument because as far as security and defence are concerned, a former prime minister of India, Indira Gandhi, had a most sophisticated defence and security, yet she was killed, assassinated, by her own security people; and perhaps the American presidents might have use sophisticated defence and security, yet some of them were also killed, assassinated.

When person comes to the end of the life the question of defence is very difficult. There is one way to look at it: first of all, to harm others for the sake of one’s defence clearly establishes that oneself is more important than the attacker or the opponent. In my view, that is very difficult to establish or that is difficult to defend. So let the attacker kill you or you defend yourself, defend your life by counter attack or counter violence; the justification of that act has to be judged from two viewpoints: what is the gain for you and what is the gain for the others. If you analyse this way, I am not very convinced of the argument of the act of self-defence. Therefore, in Buddhism we say, self-sacrifice will be much better than to indulge in violent act in order to defend oneself.

Thats the last. (laughs).

Once again thank you very much for your patience and tolerance.